Rivals, including Mozilla and Opera, also working to boost their browsers' rendering speeds

Microsoft's next browser, Internet Explorer 9 (IE9), will offload image and text rendering chores to the PC's graphic processor, one way the company plans to increase the browser's overall performance, according to the firm's top IE manager.

But Microsoft won't be alone. Rivals including Mozilla, which makes Firefox, and Norwegian developer Opera, are working on ways to use a computer's graphics processor unit (GPU) to accelerate their browsers.

Microsoft last week revealed a few details about IE9, which has no set ship date or even a publicly-disclosed development plan. While acknowledging that the company had a lot of catching up to do, however, Steven Sinofsky, Microsoft's president of Windows and Windows Live, said that early work on IE9 had already shown significant performance strides.

In a follow-up interview, Dean Hachamovitch, the general manager for IE, explained one way that Microsoft would speed up IE9.

"One reason why you get such great value from PC hardware comes from the machine's graphics, [so] we're moving IE on top of the modern Windows graphics engine, DirectX," said Hachamovitch. Specifically, IE9 will ditch Windows' GDI (Graphics Device Interface) used by earlier versions for image rendering, and instead call on the Direct2D and DirectWrite APIs (application programming interfaces) to render two-dimensional images and text, respectively.

Those APIs shift the processing from the PC's CPU to its GPU. "Graphics hardware acceleration means that rich, graphically intensive sites can render faster while using less CPU," Hachamovitch said.

Although Hachamovitch declined to peg a goal for IE9's hardware-based acceleration, he said early results have been encouraging. "On top of GDI, we were seeing IE render at 5-10 frames per second. Users don't know whether that's [caused by] the network, or a site script, but it just seems kind of slow to them. Using [Direct2D], we're seeing 40, 50 or 60 frames per second. That's game-like responsiveness."

Because the image and text rendering -- DirectWrite results in much sharper text -- is done by Windows in conjunction with the GPU, there's nothing Web site or Web application developers will have to do to make their sites seem faster to IE9 users. "Web developers can take advantage of the hardware ecosystem's advances in graphics, but don't have to rewrite their sites to do that," Hachamovitch said.

Microsoft isn't alone in exploring graphics acceleration: The top engineers at Mozilla and Opera both said that their companies are pursing the same grail.

"We have our own projects to use OpenGL on open platforms, and Microsoft's APIs on Windows," said Mike Shaver, Mozilla's vice president of engineering. OpenGL, or Open Graphics Library, is an open-source set of function calls used to render two- and three-dimensional images.

Opera, like Mozilla, doesn't limit itself to building a browser for Windows only, as does Microsoft, and so faces the same cross-platform issues as Mozilla. But hardware acceleration is coming, argued Hakon Wium Lie, Opera's chief technology officer. "We're going to see hardware acceleration across the board," Wie said. "But we can't tie ourselves to a single API, like Microsoft."

Both Shaver and Lie noted that graphics-based browser acceleration would deliver even more benefits on mobile devices, such as smartphones. Mozilla is working on a mobile version of Firefox, dubbed Fennec, while the mobile version of Opera is much more popular than its desktop sibling.

Shaver said that hardware acceleration would debut in one of the upcoming editions of Firefox, although not in Firefox 3.6, which is slated to hit release candidate status later this month and ship before the end of the year. "We'll put it in when it's ready," Shaver said. Firefox 3.7, another minor upgrade, is set to wrap up in the first half of next year, while the major upgrade to Firefox 4.0 is currently scheduled for later in 2010.

Although some have accused Microsoft of ignoring available standards -- including OpenGL for rendering two-dimensional images -- charges that have been leveled against the company numerous times in the past over other issues, Shaver and Lie refused to be drawn into that conversation. "It would be nice if we could use OpenGL on Windows, but you have to play the cards that are dealt," Shaver said. "On Windows, DirectX and Direct2D are the only reasonable path right now, so for building a Windows browser, using the DirectX APIs is reasonable. Microsoft isn't doing anything that we wouldn't be able to do."

Shaver pointed out that Direct2D was only available on Windows Vista and Windows 7, a limiting factor. Most Windows PCs, however, still run the eight-year-old-and-counting Windows XP.

"Microsoft's approach is reasonable as long as [the APIs] remain documented," said Lie, who added that if they weren't, Opera would be the first to object. Opera has done that in the past by filing complaints with European antitrust regulators over Microsoft's bundling of IE with Windows, and IE's purported lack of support for widely-used Web standards.

"Hardware acceleration will deliver extraordinary performance [to IE9]," said Microsoft's Hachamovitch, something that Shaver and Lie echoed.

"Everyone will have a better experience on the Web," Lie agreed.

11/24/2009 11:43:00 PM

11/24/2009 11:43:00 PM

kenmouse

, Posted in

kenmouse

, Posted in

Last week, Microsoft showed off some browser technology that could help Internet Explorer leapfrog the competition. But if Mozilla succeeds in its hope, Microsoft could be playing catch-up instead.

Last week, Microsoft showed off some browser technology that could help Internet Explorer leapfrog the competition. But if Mozilla succeeds in its hope, Microsoft could be playing catch-up instead.

Since Zaizai entered the Showbusiness, he had been troubled by his pronunciation problems, to broascast in Mainland, the TV drama "The Last Night of Madam Chin " had to dub his voice.

Since Zaizai entered the Showbusiness, he had been troubled by his pronunciation problems, to broascast in Mainland, the TV drama "The Last Night of Madam Chin " had to dub his voice. After "Rouge snow", "The Last Night of Madam Chin" is the second drama Fan Bing Bing produces ; to reproduce the splendor of Shanghai, she not only spent a lot of money to reconstruct the Paramount club in its original size and appearance, but also paid out to have over 100 gorgeous QiPao made, the producing fees amounting to a total of 180 Millions.

After "Rouge snow", "The Last Night of Madam Chin" is the second drama Fan Bing Bing produces ; to reproduce the splendor of Shanghai, she not only spent a lot of money to reconstruct the Paramount club in its original size and appearance, but also paid out to have over 100 gorgeous QiPao made, the producing fees amounting to a total of 180 Millions.

Microsoft has shared very few details so far about Internet Explorer (IE) 9, but has said the company is planning to accelerate the performance of text and graphics rendering by taking advantage of the power of PCs’ graphics-processing unit (GPU).

Microsoft has shared very few details so far about Internet Explorer (IE) 9, but has said the company is planning to accelerate the performance of text and graphics rendering by taking advantage of the power of PCs’ graphics-processing unit (GPU).

Apple’s 27-inch iMac did the Cupertino company proud when we reviewed the Core 2 Duo model last month, but trouble is afoot with the freshly-shipping Core i7 models. Various Apple support forum threads are suggesting that not only are some Core i7 iMacs turning up DOA and refusing to power on, others have hit desktops only for their eager buyers to discover the glass screen has cracked.

Apple’s 27-inch iMac did the Cupertino company proud when we reviewed the Core 2 Duo model last month, but trouble is afoot with the freshly-shipping Core i7 models. Various Apple support forum threads are suggesting that not only are some Core i7 iMacs turning up DOA and refusing to power on, others have hit desktops only for their eager buyers to discover the glass screen has cracked.

Now that we’ve all actually seen Chrome OS, the immediate reaction that most are jumping to is that it won’t be killing Windows anytime soon. Obviously. But that doesn’t mean it won’t hurt Microsoft, and apply long-term pressure to the dominant OS. In fact, Google’s positioning for Chrome OS reads like a page out of Apple’s playbook, only from the opposite direction.

Now that we’ve all actually seen Chrome OS, the immediate reaction that most are jumping to is that it won’t be killing Windows anytime soon. Obviously. But that doesn’t mean it won’t hurt Microsoft, and apply long-term pressure to the dominant OS. In fact, Google’s positioning for Chrome OS reads like a page out of Apple’s playbook, only from the opposite direction. ONE woman, many faces - that's Vicki ZhaoWei.

ONE woman, many faces - that's Vicki ZhaoWei. With most computers threatened by attacks coming through Web applications, it's no surprise that security would be a key piece of Chrome OS, Google's browser-based operating system that stores data in the cloud.

With most computers threatened by attacks coming through Web applications, it's no surprise that security would be a key piece of Chrome OS, Google's browser-based operating system that stores data in the cloud. After grueling months of promotion for New Moon, the Twilight cast has been finding some time to unwind in New York City. All while their li'l film dominates the box office.

After grueling months of promotion for New Moon, the Twilight cast has been finding some time to unwind in New York City. All while their li'l film dominates the box office. It was inevitable that someone would seriously consider taking Google's dare.

It was inevitable that someone would seriously consider taking Google's dare.

Rivals, including Mozilla and Opera, also working to boost their browsers' rendering speeds

Rivals, including Mozilla and Opera, also working to boost their browsers' rendering speeds ELEVEN years ago, she decided to be an entertainer.

ELEVEN years ago, she decided to be an entertainer. He's a star hockey player for the Ottawa Senators today, but Mike Fisher might be turning over a new leaf: recording artist!

He's a star hockey player for the Ottawa Senators today, but Mike Fisher might be turning over a new leaf: recording artist! Regular readers here know that I am a fan of the Windows Mobile operating system, even though that is not necessarily a popular opinion since it isn’t the flashiest and newest OS. I have talked about the strengths of Windows Mobile quite a bit and was pleased to see my friend and MoTR cohost, James Kendrick, post a fair comparison article between Android and Windows Mobile. James takes a look at multi-tasking, available apps, user interface, and computer desktop integration. It was refreshing to see James award the advantage to Windows Mobile in 3 of 4 areas with the last one being a tie.

Regular readers here know that I am a fan of the Windows Mobile operating system, even though that is not necessarily a popular opinion since it isn’t the flashiest and newest OS. I have talked about the strengths of Windows Mobile quite a bit and was pleased to see my friend and MoTR cohost, James Kendrick, post a fair comparison article between Android and Windows Mobile. James takes a look at multi-tasking, available apps, user interface, and computer desktop integration. It was refreshing to see James award the advantage to Windows Mobile in 3 of 4 areas with the last one being a tie. No word on patch plans; disable JavaScript, say researchers

No word on patch plans; disable JavaScript, say researchers Sexy Queen Lee Hyori has boarded a plane headed to NYC to formulate concept ideas for her new upcoming album.

Sexy Queen Lee Hyori has boarded a plane headed to NYC to formulate concept ideas for her new upcoming album. Cougar Town is getting back its Realtor.

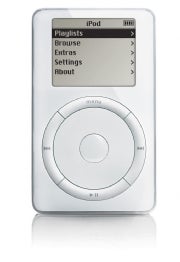

Cougar Town is getting back its Realtor. 1. MP3 Players

1. MP3 Players 2. Optical Drives

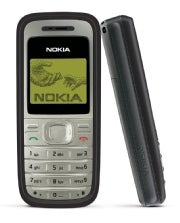

2. Optical Drives 4. Dumb Phones

4. Dumb Phones 5. Digital Cameras

5. Digital Cameras 8. Pay Phones

8. Pay Phones 9. Packaged Media

9. Packaged Media The local full-feature comedy "Happy Go Lucky" held its first day shoot ceremony on Monday without leading actress Fann Wong, who has been diagnosed as having H1N1.

The local full-feature comedy "Happy Go Lucky" held its first day shoot ceremony on Monday without leading actress Fann Wong, who has been diagnosed as having H1N1.